A study conducted in the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan (Super typhoon Yolanda), revealed that connecting with their social media contacts, particularly on Facebook, enabled survivors to make sense of their traumatic experiences and deal with emotional and psychological stress.

If a mobile phone can be a lifeline in desperate situations, an online social network can serve as an outlet for coping for disaster survivors. A study conducted in the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan (Super typhoon Yolanda), revealed that connecting with their social media contacts, particularly on Facebook, enabled survivors to make sense of their traumatic experiences and deal with emotional and psychological stress.

The study - Log in if you survived: Collective coping on social media in the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines - noted that coping is closely tied to communication. In post-disaster recovery, survivors are encouraged to engage socially by connecting with and comforting others in similar circumstances, participating in public events or volunteering for community projects, and going about their normal activities.

When traditional communication channels like radio and TV break down, such as during the typhoon, the feeling of isolation is heightened, and people turn to non-traditional information sources and communication platforms, like social media.

“We”re all alive!” This was the status update posted by a college student on her Facebook page as soon as she was able to access the internet.

A hotel owner reported that all 150-plus guests were safe, but also appealed for help as food supply was running low, as well as diesel to keep the generator running.

They are among the residents, public officials, business owners and local journalists who were in Tacloban when Yolanda made landfall on November 8, 2013, and who were interviewed for the study.

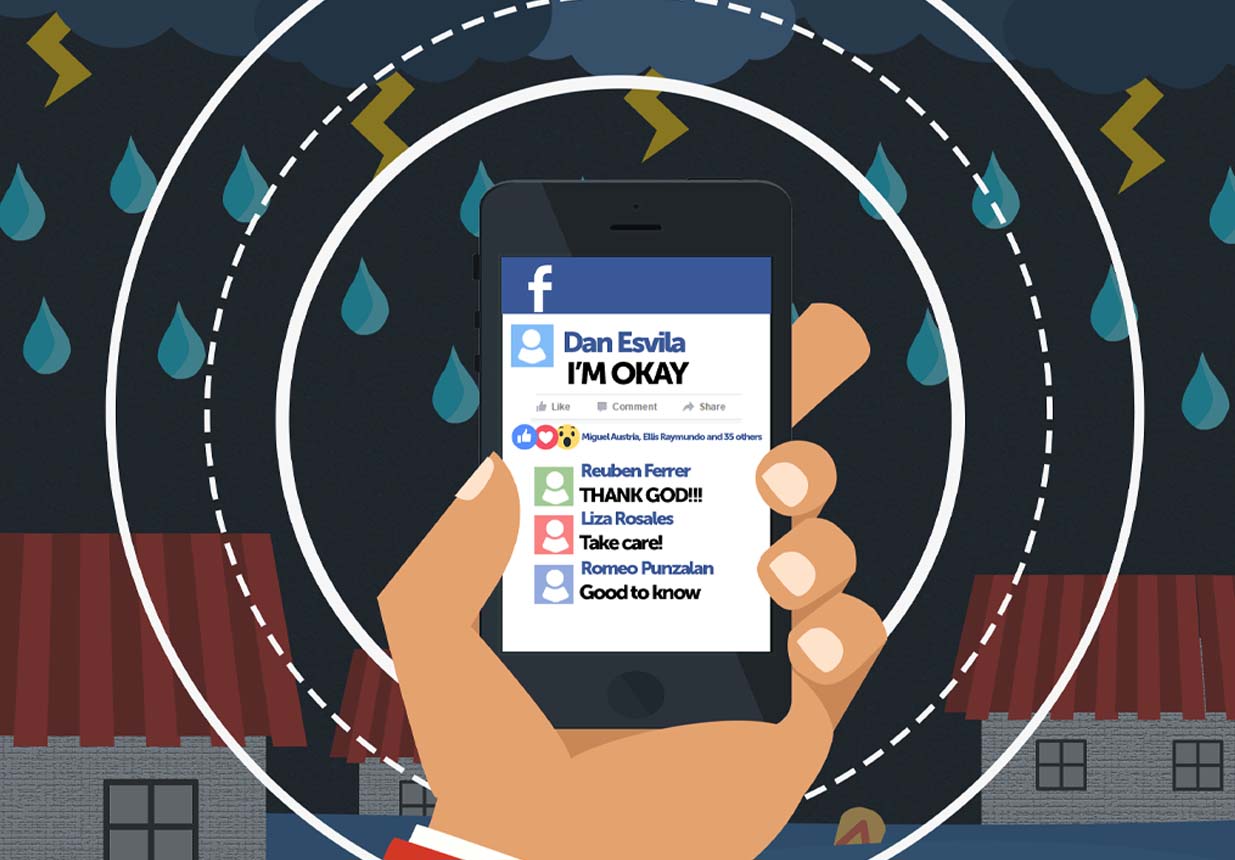

During the time, Facebook became an “inventory” of survivors and casualties, according to another respondent. “You logged in if you’re alive.”

The study was conducted by Edson C. Tandoc Jr. of Nanyang Technological University, Singapore; and Bruno Takahashi of Michigan State University, under a grant from the Quick Response Program of the National Hazards Center of the University of Colorado.

Their objective was to contribute to a better understanding of the concept of collective coping, focusing on the use of social media. Their findings offer “an alternative to many Western-centric studies that considered coping as a purely individual process.”

The Philippines, with a population of 100 million; a “largely collectivistic” culture, marked by close family ties; plus a high Facebook penetration rate of more than 92 percent, was fertile ground for the research.

The authors found three collective coping strategies facilitated by Facebook:

• a platform for survivors to tell others they survived;

• a means to participate in the social construction of their experience by airing their observations and complaints; and,

• a venue to manage their feelings and memories by documenting what they went through and how they were moving on.

In a close-knit society like the Philippines, the absence of any means of communication in the aftermath of a disaster is traumatic for both survivors, who need help, and their families and friends, anxious to know about their fate, the study said.

A tourism official walked for hours in search of a phone signal or web access, from her house to the city hall, where the Department of Social Welfare and Development set up six laptops connected to the internet using a very small aperture terminal (VSAT) antenna, in a makeshift office.

Along the way, the official passed cadavers, enduring the stench. When she was finally able to contact a cousin, she was told her that a neighbor had assured her family she was safe via a Facebook post.

Citing the technological properties of social media platforms like Facebook, the study explained their wide usage for post-disaster collective coping.

First, social media platforms allow communication on multiple levels: “one-on-one, one-to-many, and many-to-many.”

Second, social media users can open their accounts any time and access specific content from particular users at any point in their timelines, so long as the post is not set on private access and has not been deleted.

Third, social media users enjoy more personal communication, instead of “interacting” with an impersonal media organization.

Family members and friends of Facebook users are able to respond through the comments and private messaging features.

“The flooding of well-wishes on their timelines and inboxes evoked positive feelings among the survivors despite their traumatic experience, allowing a connectedness and a reassurance that others were concerned and were listening…enabling social cohesion and facilitating collective coping…” the study said.

As though to shut out all the grief and gloom, a young woman stayed locked up in her room and logged on to Facebook. Responding to messages alleviated her misery, she said.

For another respondent, a court employee, being on Facebook was “a form of stress debriefing.” She and her family were safe, but they could not easily forget what they had been through.

Other respondents’ Facebook posts focused on moving on. A printing press owner, for instance, posted that “we are now cleaning…and we will be reopening our store soon.”

Several respondents also took photos and videos of what they experienced and witnessed, “for documentary purposes…and also for myself,” as a phone company technician said.

“It wasn’t easy, though,” said a restaurant owner, “the scenes were all depressing.” Only much later did he start sharing photos on Facebook.

Similarly, a local journalist, who used her mobile phone pictures in her reports, would not look at the images again afterwards, not wanting to relive the memories they depicted. Several weeks later, she changed her mind, however, realizing how fortunate she was that she had lived to tell the story.